by Sam Goldaper

1975

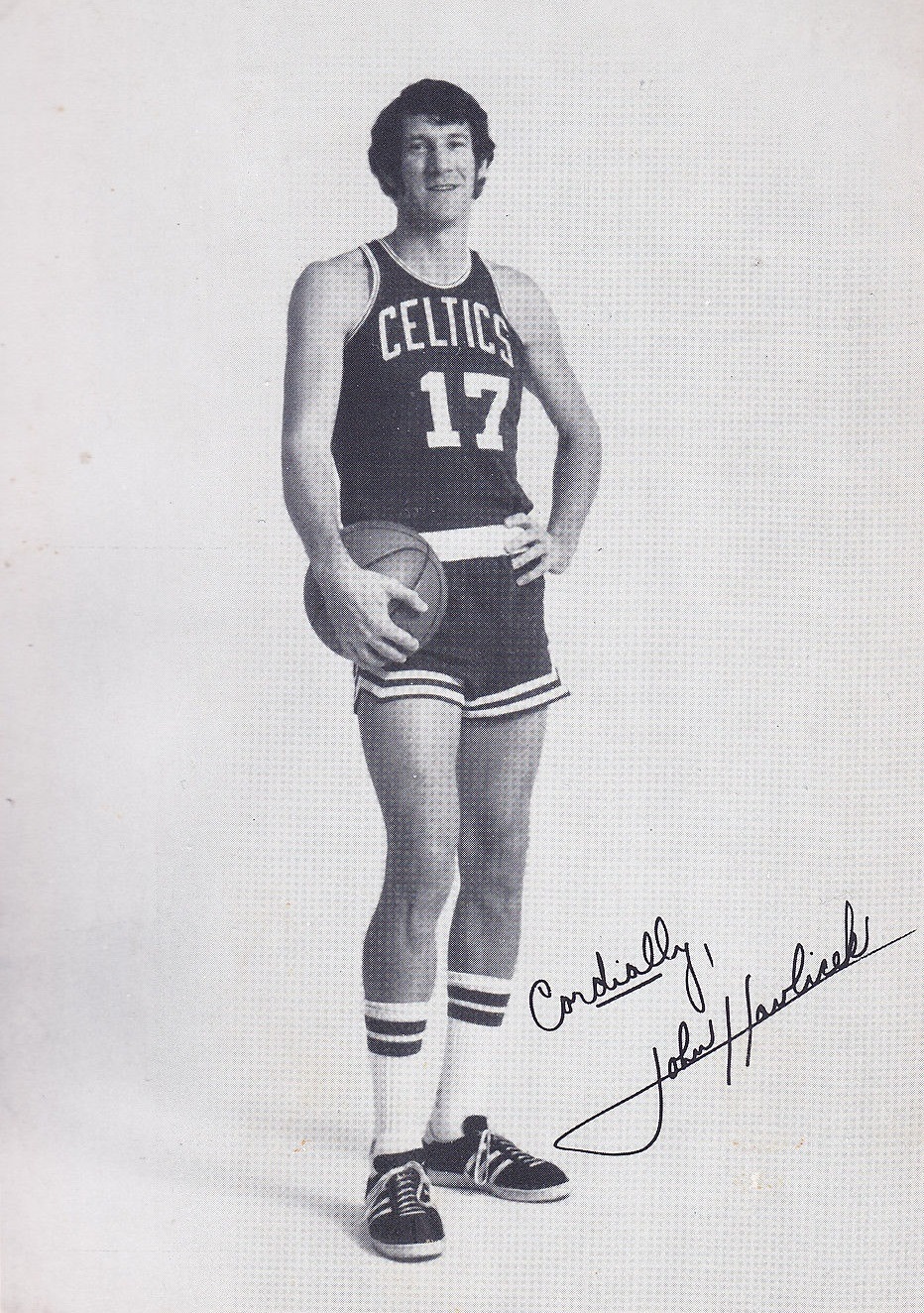

The broad and rather knobby shoulders give him a crooked look. The grin, exuding friendliness, splits a face that’s long and not quite symmetrical. John Havlicek might be the mild-mannered, bespectacled character of Clark Kent before he enters the telephone booth, rips off his clothes, and reveals his identity of SUPERMAN.

There is something out of this world about John Havlicek—whose legs move like eggbeaters during a game while he rarely breaks a sweat. If Havlicek isn’t extraterrestrial, perhaps he is the original Six Million Dollar Man, assembled by the Boston Celtics before every game in a secluded corner of the Boston Garden or in any other National Basketball Association arena. It’s difficult to accept the fact that he’s only human.

“He’s a freak,” says Jerry West, who played 14 seasons with the Los Angeles Lakers before his retirement after the 1973-74 season. “His endurance is incredible.”

Pat Riley of the Lakers adds, “There’s not a man in the NBA who can stay with John the whole game and survive. His body is made to go on forever.”

With the exception of the Boston Celtics, every team in the NBA pays its top players primarily to score in double figures, grab rebounds, block shots, or play defense. John Havlicek is hired specifically to run 48 minutes each game. The Celtics discovered years ago that the byproduct of Havlicek’s speed has not only created opportunities for John to excel but also openings for his teammates. The result is the Boston fastbreak, which has been imitated but rarely duplicated.

Case in point. There were 293 minutes of playing time in the six games of the 1967-68 championship series against the Los Angeles Lakers. Havlicek played all but two minutes. He fouled out of one game with a minute to play and was taken out of the sixth game with 38 seconds remaining. It was estimated at the time that in the sixth game, Havlicek ran almost 50 miles, scored 40 points, and then ran to the dressing room to celebrate another Celtics championship.

Havlicek is quiet, even-tempered and disciplined off the court. Bill Russell would occasionally address him as “Country Boy.” On the court, he doesn’t have the fluid grace of an Oscar Robertson, the speed of a Jerry West, the waterbug maneuverability of a Walt Frazier, or the pile-driving strength of Rudy LaRusso. But there is no other who can play the front or back court with such admirable brute force, and bouncy, unrelieved stamina. Havlicek is perpetual motion, pro basketball’s answer to Dorian Gray.

Havlicek is the last of the great Celtics. He has watched the league grow from nine teams to its current 18, and his playing days span two generations of Boston Celtics, the new, the old, and the twilight years between the two.

Like Bill Russell, Havlicek forces rival coaches to alter their method of defense. He is too fast for most forwards and too big for most guards. He’s had three pro careers. After he was pro basketball’s best sixth man, he was a combination sixth man and starter, equally at home in both the front and back court. Now, in the mid-1970s, he is a starting forward, who is still flexible enough to shift, if the occasion demands, to the backcourt.

When Havlicek first donned the Boston uniform in the 1962-63 season, the players wore black sneakers and the Celtic green was pro basketball’s medallion. He can recall when $2,000 from a playoff series would last an entire offseason. He remembers when a guy named Bill Russell introduced the art of rejection to the game and subsequently, each passing season brought a new championship flag to hang from the rafters of old and hallowed Boston Garden.

Indeed, the Boston Celtics have won 12 NBA championships since 1957, and Havlicek, affectionately known as Hondo, has been a member of seven of them. He still wears his first championship ring, primarily out of sentiment, but cherishes the 1973-74 ring the most.

The Celtics’ twelfth title, which came on Sunday, May 12, 1974, against the Bucks in Milwaukee, was immediately tabbed “the Havlicek championship.” As Havlicek walked around the Celtic dressing room, champagne dripping from his wavy hair and hugging his teammates, he told each of them, “Thanks for doing this for me.”

Havlicek Is the ultimate team man, yet deep down he got extreme personal satisfaction when the Celtics won the seventh game, 102-87. “This is the greatest one,” said Havlicek, separating this title from the six others from the Bill Russell years. The Russell teams won 11 times in 13 seasons, which was why Havlicek was so hung up on this one.

“Russell was the recognized leader in those years,” said Havlicek, who had reason to be doubly happy. For the first time in all the title winning years, he was the Most Valuable Player in the series and clearly the man most responsible for the Celtics’ first championship since Bill Russell’s retirement in 1969. “We always depended on Russ a great deal. I was just absorbed among the others.”

This was Havlicek’s team. The Celtic with a past had given as many speeches and pep talks to his teammates during the series as a candidate during a campaign. He was the catalyst between the old championship regime and the new one. He was the one around whom Red Auerbach and Tom Heinsohn had built the Celtics. “It took us five years to get this far,” Havlicek said. “I remember my first game with this group. The official said to me before the game, ‘So these are the new Celtics.’”

Havlicek gave the new Celtics direction and a steady hand during their learning years. He averaged 22.6 points during the regular season and 27.1 points and 45 minutes for the 18 playoff games. In the sixth game against the Bucks, he poured in 36 points, nine of them under excruciating pressure in the second overtime.

After the Celtics’ sixth-game loss, in which Havlicek played all 58 minutes, he appeared to be paying the price. Coming off the floor drawn and haggard, Havlicek was so keyed up that he could not unwind. “I could have played another overtime,” he has since said, “but people told me I didn’t look like myself. Afterward, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t do anything.”

Less than 48 hours later, however, Havlicek came soaring back, ready to win the final game. His recovery was partly a tribute to his resiliency and his self-discipline. “Few athletes take care of their bodies as conscientiously as Havlicek does,” says Dr. Thomas Silva, the Celtics team doctor, “and his body has seldom betrayed him.”

The Celtics’ franchise has always thrived on pride and tradition, and it became tradition not to trade or buy players, but rather to patiently develop them. The practice has been to select a player from the college draft to fill a specific need.

Red Auerbach, pro basketball’s most-successful general manager, had drafted Havlicek off the Ohio State campus to fill a need at a time when the Celtic team was a philharmonic: Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, Tom Heinsohn, Sam and K.C. Jones.

Since Havlicek scored his first two points for the Boston Celtics on a dunk shot against the New York Knickerbockers in 1962 at Boston Garden, 22,389 regular-season points have followed through the 1974-75 season. He ranks fifth among all scorers in the NBA and first among active players. Only Wilt Chamberlain, Oscar Robertson, Jerry West, and Elgin Baylor have scored more points than Havlicek. If the mechanical man, as Havlicek is often referred to, keeps running, he will overtake some of them, too.

It has been said that if the 6-foot-5, 205-pound Havlicek rolled out of bed at 2 a.m., he could take 10 shots from 20 feet out and still make half of them. A lot of guys have the reputation of putting the ball in the basket, but Havlicek is different. He plays two positions, front and back court. Sometimes he plays them alternately during a game, sometimes interchangeably.

“My game is based on speed and stamina,” said Havlicek, “wearing the opposition down. I don’t really know if you could call it overpowering them. Perhaps it’s better to say overrunning them. But I’ve always found that you’re only tired when you think you’re tired, so I’ve made it a habit to push myself when I start thinking about it. It increased my stamina, and truthfully, I can’t say I’ve ever really been tired in my life.”

To prove his point, at age 30 and nine grueling NBA seasons behind him, Havlicek, instead of following the pattern of most athletes beginning to slow down, raced at breakneck speed into the Celtic record book during the 1970-71 season in his own category—stamina. He played 3,678 minutes in 81 games, averaging 45.7 minutes a game and, coincidentally, that was his best scoring season. He averaged 28.9 points a game.

An even more satisfying milestone for someone who was a defensive-minded college player came the night of January 11, 1974 against the visiting Los Angeles Lakers. With seven minutes remaining in the game, Havlicek let fly a 20-foot jump shot to the left of the basket and became the eighth player in NBA history to reach the 20,000-point mark.

After Bob Cousy had presented him with the game ball and the capacity crowd of 15,320 at the Boston Garden had given him a two-minute standing ovation, Havlicek laughed, “After my first pro game, Jungle Jim (Jim Loscutoff) advised me in the dressing room that I would have to score more to stay with the Celtics. I never thought I would play 12 years, let alone score 20,000 points.”

Havlicek scored less in college than he does as a pro, and there is nothing mysterious about it. At Ohio State, he automatically guarded the opponent’s high scorer, big or little, with the exception of the centers. Defense was his specialty on a team that included future pros Jerry Lucas and Larry Siegfried.

Without rancor, Havlicek remembers, “Everything revolved around Jerry Lucas. Our offense was pretty much to get the ball to Jerry in the pivot. At practice, we spent 70 percent of our time on defense. When I got out of college, my big problem was developing my offense. Most rookies have exactly the other problem.”

Havlicek continues, “I was forced to learn about defense in college. Coach Fred Taylor had five guys at Ohio State who averaged more than 30 points a game in high school, so he needed a defensive forward. That was me. I became aware that movement is the most important thing on offense. If I keep moving, the defensive man is going to have to work harder. If you stay in constant motion, something is going to happen even if you run without purpose. You run to create situations.

“When I came to the Celtics, I played that role. But as you go through your career, your role changes. I moved on to replace Sam Jones as the ‘sixth man’ and then to become the guy who has to take the important shot. I have gone from being the young guy to now being the old man. In fact, I’m a senior basketball citizen. One of these days they’re going to have to find somebody else to do my job. I’m not as strong or fast as I used to be, but I’m more mature. I play with more purpose. I know when to break and turn it on.”

During Havlicek’s stay at Ohio State, the Buckeyes went 78-6, including beating California, 75-55, for the 1959-60 NCAA championship. Havlicek’s defensive ability earned him a spot on the United Press International All-American basketball team and a reason for Red Auerbach to scout him for a second time.

When Auerbach coached the Boston Celtics, by common acknowledgment, he would win NBA championships with his defense. His strategy would force ballhandling mistakes that enabled the Celtics to launch their fire-breathing fastbreak. Two coaches later, the Celtics still thrive on the same premise, while Auerbach sits in a private box at Boston Garden, still puffing his big cigars. Besides being the general manager, he is also the club president.

Ask Auerbach what he saw in Havlicek to make him the Celtics’ first-round draft choice. The man who won eight NBA championships thinks a while and says, “I scouted Hondo twice. He didn’t look especially good.” Then breaking out into a smile, he adds, “When you have the last choice in the draft, the way we had that year, you’re not particular.”

Before Auerbach called, “Boston takes John Havlicek of Ohio State,” Bill McGill, Zelmo Beaty, Paul Hogue, Chet Walker, Dave DeBusschere, Jerry Lucas, Wayne Hightower, and LeRoy Ellis had been picked. Of the eight players drafted ahead of Havlicek, not one was smaller than 6-foot-7 and several were 6-foot-9 or better.

“That’s why he was left for me,” Auerbach always has said with a sly grin.

Havlicek was entirely a Red Auerbach-type player. In fact, he was the very prototype of the 1960s Boston Celtics, one who would come off the bench, and as Auerbach has often said, “Shoot, shoot, shoot.”

Havlicek’s arrival was opportune for the Celtics. The Boston dynasty of four straight championships was showing wear. Bill Sharman was gone. Bob Cousy was going, and Frank Ramsey and Jim Loscutoff were looking for a graceful way to call it quits.

Only when you press Auerbach, and he is really serious, does he admit that, “Hondo was a hard-nosed kid, he was well-coached, he had good fundamentals. See, Havlicek was a kid that, playing second fiddle to Lucas . . . well, he’s not gonna get the ball that much. Anytime anything happens, the ball’s gonna go to Lucas. Well you can’t see too much in one or two games, so you talk to a lot of coaches and you look for the basic fundamentals.

“Then it’s guesswork. You see a kid a couple of times and what the hell can make you so sure that you’re making the right choice? Maybe he had a bad ankle that night. Maybe he didn’t eat right. One never knows.”

Nor does one ever know what possessed Auerbach to make a swingman out of Havlicek—who had never played in the backcourt. But it was a stroke of the Auerbach genius. “While Bill Russell was still around,” said Havlicek, “all I had to do against a forward was to block out. I was not too interested in getting the rebound, because if I blocked out, Bill would get the rebound. In college, I’d block out and go for the rebound too. When you’re playing guard, though, defense is tougher. Guards are much quicker, and you have to make some room to maneuver and most of the picks are coming up behind you.

“Although I regularly switched between guard and forward, most of my playing time was up front. I’d rather go without the ball. If you’re a forward, you can do that.”

Matchups are a big part of pro basketball, and as long as Havlicek plays the front and back courts equally well, he puts coaches at a disadvantage. Though in later years he has played primarily as the “small” forward, he still occasionally switches to the backcourt. For the first half dozen or so years in the NBA, a coach never knew where he would start, or if and when he would switch over from guard to forward, or vice versa. Fred Schaus, who coached the Los Angeles Lakers, credits Havlicek “as being entirely responsible for the trend to the small, quick forwards.”

Before Havlicek’s running game was put to use, the thinking was that a forward had to be big and strong. Most clubs in the league today have the small forward—Bill Bradley of the Knicks, Mike Riordan of the Washington Bullets, and Jim McMillan of the Buffalo Braves—to name a few.

Auerbach had conceived the idea of the sixth man, or the “super sub,” for the talent-rich Celtics first with Frank Ramsey, “because you need a lift from the bench, instead of a depression.” For years, Ramsey played the role of the brilliant player who always came in to contribute to Celtic championships. Ramsey was 6-foot-2, and could play front and back court, shoot, defend, steak, pass, and simply, win.

When Ramsey retired, Havlicek eased into the job as if he had been doing it all his life. He was bigger, stronger, a higher scorer, and equally adaptable. He had the right temperament to come off the bench at any time and go into high gear. Hondo did so well at being the “super sub,” that he was named to the all-NBA second team before he became a starter.

When Bill Russell replaced Auerbach as the Celtic coach, he had this joke about Havlicek. “If a forward was having trouble early in the game,” Russell would say with a cackle, “Havlicek would replace him. If the guard was having trouble, Havlicek would replace him. And if nobody was having trouble, then John can sit.”

Havlicek’s true role early in his career may have been summed up best by Phil Elderkin, writing in the Christian Science Monitor. “He plays two seasons,” said Elderkin. “In the first season, he is basketball’s best sixth man who comes off the bench cold and picks up the ballclub with his scoring and his defense. His second season is in the playoffs, in which he becomes a regular.”

While he played as the sixth man, Havlicek was used as a starter twice when the Celtics teetered on the edge of defeat. In the 1965-66 playoffs, the Celtics were losing, 2 games to 1, in a best-of-five series with Cincinnati and facing extinction on the Royals’ home court. Auerbach, then the coach, started Hondo at forward, instead of the ailing Willie Naulls.

The Celtics won, and with Havlicek remaining in the starting lineup, kept on winning to beat the Royals, 3-2. They went on to triumph over Philadelphia and Los Angeles for their eighth-straight championship.

During the 1967-68 Eastern Division semifinal against Detroit, the Celtics were behind, 2-1, in the best-of-seven series. Bill Russell, in his rookie season as coach, started Havlicek at guard in the fourth game and he poured in 35 points, as the Celtics ran away from the Pistons in the second half to win, 135-110.

Havlicek stayed in the starting lineup and the Celtics swept past Detroit in six games. But in the Eastern final, again they hung on the brink, losing 3-1 to Philadelphia. In the clubhouse before the fifth game, Havlicek wrote the figure $80,000 on the blackboard. “That’s how much we win if we all go to the finals,” said Havlicek. Below the figure, he wrote: “Pride.”

Havlicek started at forward, replacing the injured Satch Sanders, and Hondo recalls, “Russ came to me and said he wished he had two of me, one for the backcourt and one for the front. I said he’d have to be Houdini to cut me in half.”

There were times when the 76ers and the people watching that series thought Russell might indeed have cleaved Havlicek in two. He led the Celtic scoring with 29 points and helped drop 20 more in with 10 assists as Boston won, 122-104.

The Celtics evened the series at three games each, 114-106, and Hondo was the high scorer with 28. He collected 21 points in the game that put Boston into the final against Los Angeles.

Russell kept Havlicek in the starting lineup in the series against the Lakers. Running—and then running more—Havlicek ruined his reputation as the best sixth man in creation. He averaged 25 points, 10 rebounds, and seven assists a game as the Celtics won their 10th championship in 12 seasons.

When Auerbach was once asked if he ever had the temptation to start Havlicek in the early days of his career, He said, “Oh, the temptation was always there, but you need a lift from the bench, and Johnny practically ran himself out of that chance to start. You couldn’t believe a guy could keep going on like that. And once you put him in, you couldn’t take him out because he never stopped. I always was afraid he might get tired at the end, when I really needed him, if he started.”

Havlicek was different from the other Celtics and unlike most of the small-town kids from Eastern Ohio. He was born on April 8, 1940 in Martins Ferry, lived in Lansing, went to Bridgeport High School, picked up his mail in Adenna, and hung around the family store in Dillonville, eating butter sticks when most kids thrived on candy bars.

“I ran everywhere when I was young,” said Havlicek. “I ran to the store, to school, everywhere. That way I had more time to play ball. If I had to do an errand, I’d get it done quicker. I’d run home from school for my lunch, and I’d run back after lunch. I knew just how long it should take me, 45 seconds. With about 12 minutes for lunch, I’d be back on the playground in 15 minutes, which gave me 45 minutes to play before class. I was always wrapped up in some kind of ball.”

The area that Havlicek grew up in was dependent on steel manufacturing and coal mining. The people were Eastern Europeans. John’s grandfather had immigrated to those coal mines from Czechoslovakia, setting up a grocery store. John’s father, Frank, worked in the family store and, until his death in 1973, he never lost his accent or the belief that soccer was the only real sport.

Havlicek was an all-state quarterback at Bridgeport High School, where the team was known as “Big John and the Seven Dwarfs.” “Our line averaged 135 pounds a man,” Havlicek recalled. “We usually were outweighed by something like 80 pounds a man. But we were quick, and you didn’t know what we would do next. I threw a lot of passes, and we had razzle-dazzle plays and a lot of belly-series stuff.

“I was real good at faking the ball on the belly-series. Once, I rode a guy into the line and then took the ball away from him. He was tackled, and the referee blew the whistle, blowing the play dead. The referee was still looking for the ball when I took over and handed it to him.”

Bridgeport won and lost about the same number of games in John’s senior year, though the basketball team had a 17-1 record and Havlicek was an All-State forward. Once, after he had scored 28 of his team’s 31 points in one game, the rival coach told everyone he knew how to stop Havlicek. “Put three men on him man-to-man, and play the other two in a zone under the basket,” he said. “And every time he gets near the ball, complain to the officials that they’re favoring him.”

Havlicek also played first, second, third, and shortstop for the baseball team, hitting between .400 and .500 every season. Havlicek’s baseball teammates were the Niekro brothers, Phil and Joe, who later became outstanding Major League pitchers. “I think John could have made it in any sport he tried,” Phil Niekro once said. “He was a heckuva quarterback, and I always thought football was his best game.”

The first time Havlicek got a real glimpse at the outside world was when he went to play in an all-star basketball game. “It was there that I met Jerry Lucas and Larry Siegfried,” said Havlicek, “and we became good friends. Five members of that all-star aggregation went to Ohio State, including Mel Nowell. One day, Mel went to see John Wayne in the movie, Hondo. He couldn’t pronounce my name, and he said I looked like John Wayne from the side, so Hondo became my nickname.”

When Havlicek headed for Ohio State, he left an everlasting impression on his college coach, Fred Taylor, starting with the day he walked into Taylor’s office and said there was “only one basketball, and you’ve got plenty of guys who can shoot it. I’m going to make this team on the other end of the floor.”

Taylor said at the time he was trying to sell his team on defense. “Defense is not something easy to sell,” said Taylor, “but here was John literally jumping at the chance. I had never seen anything like it before. And, of course, I never saw anything like John.”

The Buckeyes would go through a two-hour conditioning program before practice began. On the final day of the program, the players had to run a cross country mile in under six minutes. “I would do it in 4:50,” Havlicek remembers. “I used to run across the golf course and keep up with the guys on the track team.”

When he graduated from Ohio State in 1962, Havlicek gave pro football a shot before basketball because it looked a little easier. “The football season is shorter, too,” he said. “About 20 football games is a lot shorter than having to play 100 basketball games. I did things in basketball that pro football coaches would carry over to pro football as a wide receiver. I was quick, had good moves, and good hands.”

Not having satisfied his urge to try pro football, Havlicek accepted the offer of an automobile and a $15,000 contract to report to the training camp of the NFL Cleveland Browns. “I wasn’t planning to do much talking in that first day in camp,” said Havlicek. “I heard about the things they did to rookies in pro football. Suddenly I began to hear these barking and growling noises, like maybe they were meant for me. When I looked around there was this huge guy with two T-bone steaks on his plate. He was eating them raw.”

As a wide receiver and later a flanker, he scrambled through five weeks of preseason practice. The coaches called him “The Spear,” and thought he was better at catching a football than throwing one.

The Browns elected to keep four receivers, and Havlicek was the fifth. Rather than cut a veteran—or Gary Collins, another draftee that year with a no-cut contract—they cut Havlicek. “I thought I had the best hands in football camp,” Havlicek still maintains. “Not too many disagreed with me. I had to run the 40-yard dash twice, because the first time I ran a 4.6, and they didn’t believe it.

“Paul Brown (Cleveland coach) put me in for only a few plays in one exhibition game against the Pittsburgh Steelers.” Havlicek recalled with a wide grin. “On the first play, I was flanked to the right. It was an end sweep for Jim Brown. It was one of those picture things. I cut down the defensive halfback, and Brown went for 48 yards to the two yard line.

“On the next play, from the two, I was the tight end. The play was to come off my left hip. I looked across the line, and there, facing me, was Big Daddy Lipscomb,” at more than 300 pounds.

“A lot of thoughts crossed my mind,” Havlicek said, “like leaving the ballpark. I sort of blasted straight ahead. Big Daddy grabbed people and sorted them out and then grabbed the runner. I ended up on the bottom of the pile, my helmet knocked half off. But on the next play, we passed for the touchdown.

“The next time we had the ball, I was a decoy on the flank. I ran my patterns, but no one threw to me. And that was it. I didn’t play anymore.”

Havlicek put those great hands on the wheel of his brand-new 1962 Chevrolet Impala convertible, the bonus from the Browns, and drove to Red Auerbach’s basketball camp in Marshfield, Mass. It was no joyride. His failure to make the Browns—his only failure in sports to this day—bothered Havlicek.

“I was crushed,” he recalled. “I felt the Browns had made a mistake. I felt I could really play. The Houston Oilers, who were in the old American Football League then, made a pitch for me, but I felt if I was cut by the Browns, then the Good Lord was trying to tell me something. I decided to stick to basketball.”

Auerbach wasted little time putting his first-round draft choice through a workout. “We had him work against some of the guys,” recalled Auerbach, “and John just ran up and down the court without taking a breather. He jumped and shot, and I watched with awe. I was stunned. After three minutes, I knew we had bought something good, something very good. Ben Carnevale, who was then the coach at the United States Naval Academy, was my assistant in camp. We looked at John. Then I looked at Ben, and Ben looked at me. I remember Ben saying, ‘Holy Bleep, look what we got.’ Havlicek was a pro from the day he joined us. You can scout more watching a scrimmage than watching a game.”

The Celtics’ original offer to Havlicek was $9,500 with no bonus. Since the Celtics were dominating the NBA, Havlicek was told, “your bonus will be the playoff money.” Unknown to Havlicek, Fred Taylor had called the late Walter Brown, the then Celtic owner, and asked for a better financial deal. Brown was reluctant at first and told the Ohio State coach, “You college coaches are all alike. You always think your player’s worth more.”

Taylor remembers telling Brown, “The NBA never had a player worth more than this one.”

The Celtics finally agreed to a $15,000-a-year contract, and Hondo quickly established his marathon style. Havlicek’s first Celtic training camp was at Babson Institute in Wellesley, Mass. The Boston players looked him over and, after one drill, they quickly named him “The Spider” because he seemed to have eight arms and legs and was light enough to sleep in a cobweb.

They also introduced him to the fact that pro basketball is a contact sport. Jim Loscutoff, who was pro basketball’s answer to a middle linebacker, was the teacher in that department. Bob Cousy, who could run a little himself, decided to test the new guy’s endurance. Both were quickly surprised.

“Jim must have weighed more than 25 pounds more than me in those days,” recalled Havlicek, “and he let me know it. In the first scrimmage and in subsequent intra-squad games, he would go over my back. I figured a referee would call that in a game, but I said nothing. Instead, I responded to his intimidation by running.

“One day, Jim, panting real hard, said to me, ‘Man, you run too much. Nobody runs like that. Slow down.’ I told him that if he would quit pushing me around, I’ll quit running so hard. He didn’t climb on my back so much after that.”

Cousy, working on the premise that “every man has his breaking point,” arranged that Havlicek would play on his team in the intra-squad game that day. “I’m going to run him and run him and run him,” Cousy said at the time.

Well, he had Havlicek running like a scared politician. Sure enough, it turned out Cousy was correct. Every man has his breaking point, but it was Cousy who ran out of gas. In disgust, Cousy threw the ball at the rafters and yelled, “The hell with it.” A rookie on any professional team needs a friend. From then on, Havlicek found one in Cousy.

Havlicek has said he can remember his first Celtic camp and season as if they were yesterday. “I was absorbed right away,” said Havlicek. “There was no trial period. No feeling out. Red never took a lot of guys to camp, and the old Celtics knew what to expect. All Red did was motivate them. His idea of a team having character was as important as anything else. He was gruff and tough, but he transmitted something. He instilled a feeling of unity, a feeling for each other. We like to call it Celtic pride.”

During his rookie season, Havlicek was a replacement for Bob Cousy, K.C. Jones, and Sam Jones in the backcourt or for Tom Sanders and Tom Heinsohn up front. “I divided my playing time with Frank Ramsey,” Havlicek said. “Frank was near retirement but still great, and we became very close friends. That’s when I first got to be called the ‘sixth man,’ and Red would say, ‘It doesn’t matter who starts, it’s who finishes the counts.’

“I always wanted to finish, and have taken great pride in my ability to play both the front and back courts. No one else has really done it. Usually, a sixth man can handle the offense at either position. It’s the defense that separates us. A guard can’t always pin the good forward in the corner, and a forward can’t stay with a guard racing up and down the court. I was able to do both because my collegiate defensive background made it easier.”

At first, Havlicek’s offensive game consisted of a pass to Bill Russell in the pivot and an awed look at teammates Sam Jones and Cousy. When Bill Russell hit him with a pass, Havlicek would shoot. “Then they started to sag off on me, and I couldn’t do it anymore,” Havlicek said. “It took a good scolding from Red Auerbach to wise me up. I remember Red telling me, ‘You can’t let them insult you. They sag off when you’ve got the ball ‘cause they know you won’t shoot.’

“Red only had to tell me once. Because of the team’s running style and my own natural ability, which nobody knew about, I started to score.”

The other part of Havlicek’s game that needed help was his ability to get off his passes. Bob Cousy’s teaching took care of that. “Cooz took me aside and told me I was over protecting the ball,” said Havlicek. “He told me if I didn’t stop turning sideways to the man who was guarding me, I would never get the ball over to a teammate. Cooz suggested I practice using my left hand as a well as my right hand in bringing the ball up the floor against the man guarding me. Otherwise, I’d never be able to properly see the open man.”

Havlicek averaged 14.3 points a game and was named rookie of the year for his all-around play. He logged the most playing time, with the exception of Russell and Sam Jones. He was also fourth in rebounds and fifth in assists. Most important for Havlicek were the testimonials from his teammates and the opposing players whom he ran ragged.

Frank Ramsey called him “one of the greatest rookies to come into the league.” Bob Cousy predicted, “John would have a long and outstanding career,” and Bill Russell added, “John’s game is work, hard work . . . which, of course, endears him to me.”

Those were the old vintage Celtics talking about Havlicek. Nothing has changed. When Dave Cowens, who runs the fastbreak alongside Havlicek, came to his first preseason camp prior to the 1970-71 season, it was no different than in 1962.

“I remember the first day of preseason camp,” said Cowens. “I had never met John, but in my first practice session, he started going full speed immediately, despite not having worked out during the summer. The rest of us were huffing and puffing. It just went out and set us an example.”

In future seasons, game after game, Havlicek physically beat some of the best-conditioned athletes in the world, guards and forwards. It’s easy to find ballplayers who are willing to say nice things about John Havlicek. Even off the record, the people who know him still surround his name with superlatives and marvel at the way he continues to run.

Harthorne Wingo, called up from the Eastern League by the Knicks midway through the 1972-73 season, learned about Havlicek’s stamina the hard way. Wingo had the misfortune to be matched against Havlicek. Hondo ran him into exhaustion until coach Red Holzman pulled his rookie out of the game to save him from further embarrassment.

On the bench, Wingo turn to Dick Barnett and said, “Man, I don’t believe it. Thirty-two years old and the cat runs me off the court.”

Barnett gave Wingo one of his heavy-lidded stares and said, “If you had what he has, you could do it too.”

Wingo gave Barnett a dumbfounded look and asked, “What’s that?”

Barnett replied, “Three lungs.”

Following Havlicek’s outstanding rookie season, he went back to Columbus and practiced every day with Siegfried, Lucas, and Oscar Robertson. He worked on his shooting and ballhandling with jaw-dropping results. Havlicek astounded the Celtics at the start of his sophomore season. Tom Heinsohn made this observation: “They say you can’t learn to shoot, but when John came back for his second season, he was knocking the eyes out of the basket.”

Havlicek paced Boston in scoring with a 19.9 average. It was the Celtics’ first championship after Bob Cousy had retired. Hondo has been either the first or the second-leading Celtic scorer ever since. “I played mostly guard that season,” said Havlicek. “I learned to keep my head up while I was dribbling. That’s really the essence of basketball—keeping your head up, knowing what’s going on, seeing the open man. That’s the stuff Cooz tried to get across to me in my rookie season.”

Havlicek, who gives the impression that he never really left the farmlands of Ohio, tries to go ahead with his job with as little pomp as possible. For a man who has played in 1,033 regular season, 148 playoff, and 10 all-star games through the 1974-75 season, he has made it impossible to pinpoint his greatest moment.

“I don’t think I lead by my words,” he says. “Athletes respect ability, and the people who have been around the longest get the most respect. It’s a matter of your character and style of play, and your ability to perform when it’s difficult.”

Still, an important aspect of sports is to live in the past, compare and argue that one player or team is or was better than another. Sports historians have recorded the night that has been tabbed, “When Havlicek Stole the Ball,” his 54-point performance against the Atlanta Hawks, and the sixth game of the 1973-74 playoffs against the Milwaukee Bucks, as some of his greatest moments.

They were separated by a span of almost a decade, long enough for an entire generation of young basketball fans to grow up without knowing what it was like on Thursday, April 15, 1969, in the Boston Garden, as the final seconds ticked off in the seventh game of the Eastern Conference playoff final against the Philadelphia 76ers.

The Celtics and 76ers had split the first six games, each winning on the homecourt. In the seventh game, the Celtics led by 15 in the first period, and Philadelphia led by one at halftime. The Celtics had a 10-point lead in the third period, and then the game came down to the final three minutes.

As the scoreboard read: Boston 110, Philadelphia 103, Wilt Chamberlain rose to the occasion. He tipped in a basket and sank two free throws to cut the Boston lead to three with 31 seconds remaining. Sam Jones had the ball and was dribbling it around the court, killing time in the finest tradition of Bob Cousy. “What I really planned to do,” said Sam Jones, “was use up 22 seconds and then heave the ball up into the rafters, but I couldn’t judge the clock.”

Instead, the 24-second buzzer went off, and Philadelphia had possession with seven seconds remaining. The Sixers got the ball into Chamberlain, and Wilt stuffed it. The Boston lead was down to one point with five seconds to go, but the Celtics had the ball out of bounds. All they had to do was to throw it in, hold it, and they would reach the NBA Finals against Los Angeles.

But Bill Russell, throwing the ball in, hit the guide wire to the basket—a fantastic accident—and it was Philadelphia’s ball out of bounds. A pass into Chamberlain, a basket—the Celtic reign would have been over. Then came John Havlicek, like a knight in shining armor, to save the game.

Philadelphia put the ball in play under its own hoop. The 76ers called for a play in which Hal Greer would pass the ball to Chet Walker, who was being guarded by Havlicek, then take a return pass from Walker and shoot from behind his screen.

Greer took the ball, and the Sixers set up. “I figured when Greer didn’t get the ball inbounds in a hurry, he wasn’t going to make a long pass,” said Havlicek. “I had a hunch he was going to pass to Chamberlain, so I set myself in position where I could defend against the pass to Wilt or to Chet.”

Russell and Chamberlain faced each other under the basket. “From his eyes, I knew it was going to be his play,” said Russell. “I got ready to put my weight against his. For all the marbles. For all the money, the MVP trophies and the all-star games and all the rest of it.”

Greer threw the ball in for Walker, and then . . .

“I don’t know where that guy came from,” said Hal. “I saw two other Boston guys, but I knew they couldn’t do anything. I think that guy must have come from the other side of the floor, because I never saw him.”

“That guy” was Havlicek.

A split second after Greer threw the ball, Havlicek leaped. He didn’t try to intercept the ball. He simply taped it to Sam Jones, and Sam took off dribbling downcourt. Meanwhile, in the radio booth, announcer John Most in the dulcet tones that could break a pane of glass 100 miles away, was screaming, ”Havlicek stole the ball. He stole the ball. He stole the ball. The Celtics win. Havlicek stole the ball.”

Everyone has come to expect big things from John Havlicek, and on April 1, 1973, he opened his ninth playoff season with undoubtedly his greatest shooting night. He banked, swished, and probably willed 54 points in 31 minutes of playing time, into the basket as he led the Celtics to a 134-109 victory over the Atlanta Hawks at the Boston Garden. Havlicek hit at an unbelievable 24-for-36 pace, all on jump shots of 15 feet or more.

The crowd of 11,907 rooted him on in the final period as Havlicek closed in on the magic 50-point mark. Judging from the reaction when someone other than John took a shot, it appeared there would be a mass riot if his teammates didn’t start setting him up. The amazing thing about his effort was that he got his points strictly in the flow of the game. “The only time,” said coach Tom Heinsohn, “we ran a specific play for him was for the basket that broke the 50-point mark.”

On that occasion, the team broke out of an inbounds play into their favorite backdoor routine, and Dave Cowens fed John perfectly for an unmolested layup. Havlicek’s reaction to his 54 points was one of expected modesty and credit to his teammates. “I had the opportunity to move and our fast break worked,” Havlicek said. “I have to move without the ball, and tonight my knees felt good. The best since midseason.”

All anyone is going to remember about Havlicek from the Milwaukee championship series is the historic sixth game, the fantastic double overtime Bucks’ victory won by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s corner hook with three seconds left. Until Abdul-Jabbar came up with that amazing shot, the story of the game had been Havlicek.

With the largest television audience in NBA history watching, Havlicek put on one of his greatest clutch shows. He tied the game in the first overtime with a standard hustle play. Milwaukee had the ball and a two-point advantage, but the Celtics stole it back with 13 seconds remaining. The ball came to Hondo, and he took a stop-and-pop jump shot from inside the foul line and missed. But Havlicek kept right on going and got his own rebound. He shot again and tied the score at 90.

It was just setting the stage for the second extra session show in which he scored nine of his team’s 11 points, including two almost incredible baseline turnarounds he somehow lofted over the stretched Abdul-Jabbar. When he swished the second one, it gave the Celtics a 102-101 lead with seven seconds remaining. It seemed inconceivable that somehow fate would not permit him to be a hero after all he had done. Seconds later came the Abdul-Jabbar winning basket.

Havlicek, who has seen hundreds of players come and go in the NBA, was asked to compare the new and the old Celtics and the league’s changing guard.

“The Celtics, new and old, are very different,” says Havlicek. “The difference isn’t only because of Bill Russell. They are just different kinds of players.

“The players today are physically much more talented, but the teams aren’t really as fundamentally good now. They have so much raw talent they are able to get the job done. The values of the players are a lot different now. I’m not trying to downgrade this generation, but I’ve seen both sides and people today don’t work as hard towards the goals we used to work at.

“The Celtics of today get along well. They score as well as the old Celtics, but the defense is not as good. We don’t run many patterns. This is strictly a fastbreak team. We always ran the fastbreak, but then we ran patterns, too.”

During the 1974-75 season, the enduring Havlicek’s 13th, he has lost a bit of his jack-rabbit quickness and some of the bounce out of his knees, but Hondo still played in all 82 regular-season games and still confounded opponents with his unflagging stamina.

Bill Russell, once watching Havlicek demolish the Knicks at Madison Square Garden, said, “The man is crazy. One of these days he will find he can’t do that anymore.”

In response to Russell’s statement, Havlicek laughed and said, ”Yeah, Bill’s right, but I don’t know when it will happen.”

When it does happen, John Havlicek’s No. 17 will be retired, and his number will be placed high in the rafters of the Boston Garden along with those of Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, Sam Jones, K.C. Jones, Satch Sanders, Tom Heinsohn, Bill Sharman, and Frank Ramsey. And someday John Havlicek, the Green Running Machine, will also make it to the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass.

***

John Havlicek AP Images Pictures

https://www.apimages.com/Search?query=John+Havlicek&ss=10&st=kw&entitysearch=&toItem=15&orderBy=Newest&searchMediaType=allmedia